What is better or worse for literature? The quiet tyranny of prizes or the constant demands of the market. Between both poles, the writer digs the hole like a mole. To be somewhere, or to be nowhere. Yes, the nowhere sections exist—who ignites Kafkaesque—those that don’t seek submission or praise, but the pyre—where he drops his dark pages.

And in the end, what matters? If you watch closely, you will see that fashion changes, façades shift, and surface sketches crack away, experiments extinguish—what dares to surpass centuries: depth born of feeling.

In the Victorian era, the pressure points were different; they came mainly from the market. Chapters had to be delivered on schedule, with the right mixture of drama, sentiment, and cliffhangers to keep the readers buying the next issue. Editors counted words; readers actively participated and wrote their opinions. In Charles Dickens’s serialized world, even a single reader could sway the plot. A housewife in Manchester once wrote to him, pleading that her favourite character be spared. The letter crossed the country and landed on his desk while the story was still unfolding. In such moments, the market was not an abstract force but a voice in the writer’s ear. This was the world in which Oliver Twist and Bleak House germinated—one eye on the story, the other on the calendar. Now, that calendar—once marked in red for every deadline—lies blank, replaced by the long, slow clocks of the prize era.

If we prod the plot, the compromises come crystal clear: padded subplots, sentimental deaths, moral safety for the circulating libraries. Yet Dickens is a legend. Why? He was no exception to contemporary literary policies. His concessions were in form, not in depth or soul. Characters breathed lively, moral threads were woven so deeply that time filtered out the padding and left the fire burning. What was once a commercial strategy now looks like structural genius.

Now the scenario has changed. Here, the danger is not overwriting but overpolishing. It is not a Friday night show to allure the audience, but the main pitch is small jurors sitting in a well-lit room. Kiran Desai is publishing her novel in 2025, after her Booker-winning book in 2006. The same was true for Arundhati Roy. The pressure of the past has made the writer’s womb endure a long gestation period. The writers instead adjust to the public mood, trying to match a certain prize-season tone: lyrical but not too obscure, topical but not too raw, ambitious yet recognisable to critics.

When it works, it can produce masterpieces—but the prize culture has its quiet harm. Risk-taking may narrow to the fashionable kind; spontaneity can dry up under the weight of perfectionism. A prize book may win headlines in October and be forgotten in a decade, not because it lacked skill, but because it never found the larger heartbeat that lives beyond its moment.

Between somewhere exists a third breed who belong to nowhere. They don’t write for mass, nor for class. I call it the Kafka niche. He belonged to no camp; he had no mass readership, no prize ambitions, and little interest in the machinery of fame. His books were often left unfinished in drawers, his audience a small circle of friends in Prague. This gave him total artistic freedom, but also near-complete invisibility. At his death in 1924, only a few slim volumes and scattered magazine pieces had been published.

Then came Max Brod, the friend who ignored Kafka’s request to burn his manuscripts. Within three years, The Trial, The Castle, and Amerika were in print. Critics in Germany and France began to see in him a prophet of modern alienation. Translations by Edwin and Willa Muir brought him into English, albeit in a softened Biblical cadence. The Second World War made him newly relevant: here was the writer of bureaucracy, faceless authority, and the fragile self.

By the 1960s, a new word had been invented in the dictionary—Kafkaesque. Franz Kafka’s work, which had neither mass-market serialization nor prize-court polish, began to shape writers from Camus to Márquez. Eccentric ink, with incomplete structures—but weighing the everlasting emotional truth—so much that they crossed boundaries and decades without losing their charge. It was the time when the real line was drawn. Structure and experiment matter—they are the shape in which a work reaches us—but they only endure if the feeling is alive. Strip away the form and then ask—what remains? If the naked core is deep and emotive, then the work will outlive the fashion.

Shakespeare proved it. He wrote for the Elizabethan stage; the commercial entertainment was carefully, cautiously built. It would be interesting to know that if King Lear were written in Beckett’s sparse prose style or postmodern fragmentation, would it survive? I certainly think so. Lear’s howl over Cordelia’s body, Hamlet’s paralysis in the face of revenge—these are not technical effects, but recognitions of the human condition. They would have made their presence in the bone-dry, minimalist fabric—powerfully.

I have felt these pressures in my own small way. While working on my manuscript Kashi, I sometimes caught myself wondering: which path am I walking? Am I writing for the instant pull of a mass connection, or am I polishing towards the slow prestige of an award? On some mornings, I stopped thinking about either and just tried to hear the exact sound of a scene—the way a mother’s voice bends when she calls her son to dinner, the particular glisten of Govind Bhog rice beside a curry. Those days felt the most honest. And perhaps honesty, in art, is another word for depth.

Charles Dickens’s mass fame, the prize author’s prestige, and Kafka’s posthumous ascent—three paths, three compromises, three kinds of survival. But the works that live longest are those where feeling has driven the structure, not the other way around.

This is the bridge every writer must find: between the crowd and the critic, between the demands of the day and the slow echo of the heart. Market and prize can both serve the work or distort it. They are only the scaffolding. The cathedral is built from something else—that moment of pure connection when the writer’s truth and the reader’s truth meet, and both recognise themselves in the other.

If a book can stand there, it will stand for a long time.

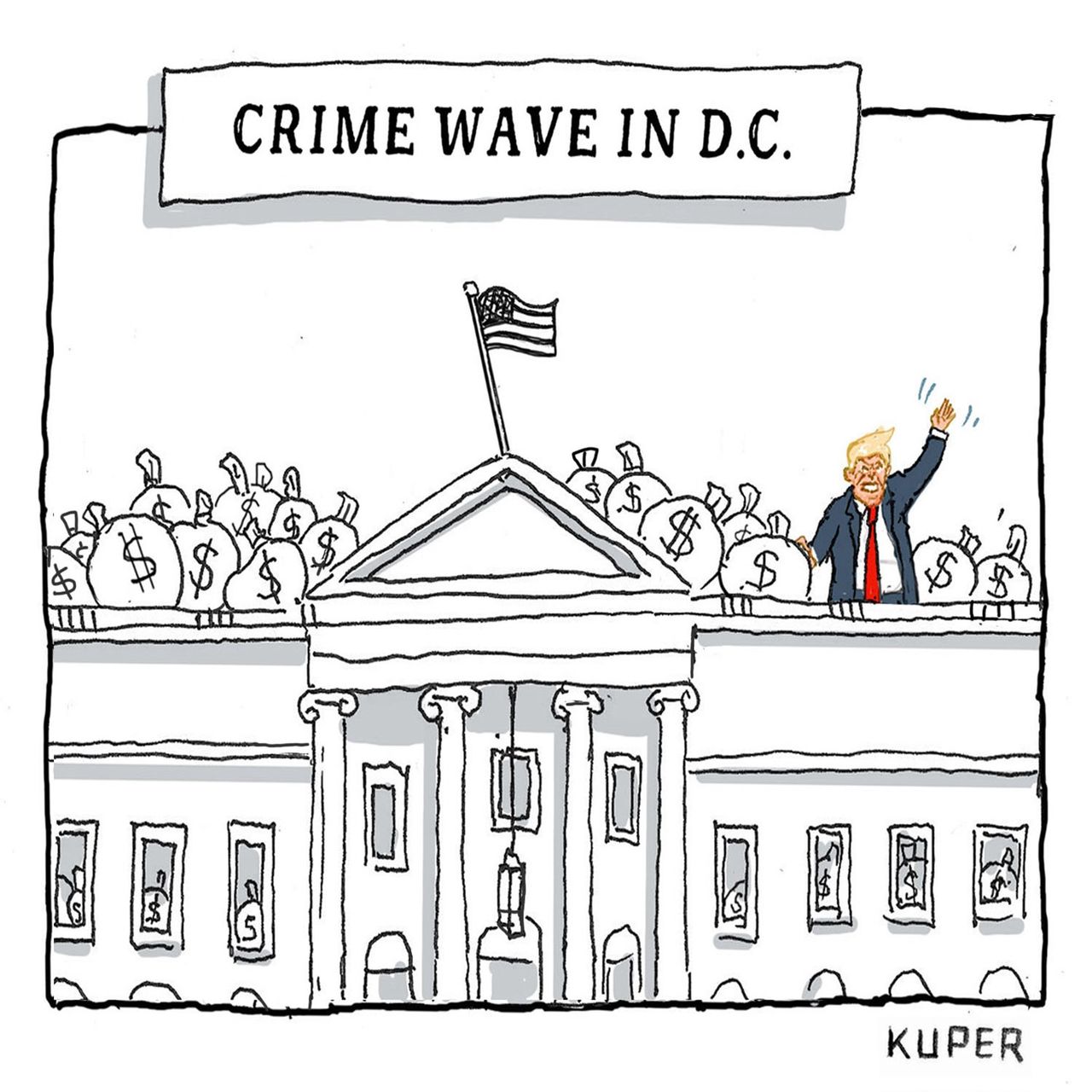

Satire Snapshot — The New Yorker

Pragya’s Pen — Where words find their temple

Leave a reply to Pragya’s Pen Cancel reply