What happens when a saint takes the reins? He spreads nothing but chaos and heaven loses its silence.

Tolstoy’s letter to Gandhi in 1909 was written like a benediction sent from the last twilight of one saint to the dawn of another. Both men saw the same dream — the kingdom of God on earth — yet both forgot that the kingdom of God begins where history ends.

History is the recycling jumble of human events — politics, wars, reform, social change, ambition, and decay. It is the world of action, ego, and consequence — what the Gita calls karma-kshetra, the field of deeds. But the kingdom of God, in Tolstoy’s and Gandhi’s sense, is not historical; it is spiritual. It begins when that restless motion of history stops inside the individual — when desire, power, and pride fall silent.

In other words, heaven is not something you build within history through reform or revolution; it is something you realise when you step beyond the noise of history. Yet both negated history in their spiritual preachings and remained wrapped in contemporary events, only to become history’s men in the future. They were contradictory creatures who first engulfed their families and then the world.

Both Tolstoy and Gandhi tried to create heaven on earth through social and moral effort — but heaven, by its nature, starts only when the machinery of human history ends.

Their friendship was brief, spiritual, and doomed, for it tried to unite two opposite currents: the yogi’s inward silence and the reformer’s outward cry. In that letter, Tolstoy told Gandhi that love and truth were the only laws of life, and that resistance to evil must be passive, not violent. Gandhi was deeply moved; he called Tolstoy his teacher and named his South African commune Tolstoy Farm. Yet that seed of moral idealism, once planted, soon grew into paradox.

Both men had families, both were surrounded by the raw dust of domestic life — wives, children, money, disciples — yet both declared the world an illusion. To preach renunciation from inside a household is like lighting incense in a storm: the smoke turns inward, choking everyone nearby.

A true yogi looks within and negates the outer world; he does not attempt to reform it. Kabir, Tulsidas, Sai Baba — they kept themselves in sambhav, the stillness beyond joy and sorrow. They neither entered the courts of kings nor moralised the masses. They saw the world as a passing dream and let it dissolve. But Tolstoy and Gandhi tried to moralise that dream — to spiritualise politics, to weave God into the cloth of governments. And so, like tragic saints, they tore the fabric of their own lives.

Both were fathers who preached celibacy, creators who despised creation. Gandhi fasted three days for a youthful kiss; Tolstoy tortured his wife with sermons on chastity while she raised their children alone. They transformed private guilt into public morality. Their moral experiments, instead of cleansing the world, filled their own homes with dust and despair. It was the ancient yogic fire misapplied to the material world — moral anarchism disguised as holiness.

The Kiss that Launched a Fast

In South Africa, Gandhi’s son Manilal, barely a teenager, kissed a girl. It was a moment of innocent warmth — the natural rebellion of youth discovering tenderness. But for Gandhi, it was thunder. He announced a three-day fast to purify the ashram and his household. The father who preached compassion now stood as a judge of instinct. What might have been an intimate lesson of growing up became a public ritual of repentance.

This episode, small yet volcanic, reveals the same tension that consumed Tolstoy — the attempt to moralise life instead of understanding it. Both men sought to purify the body by denying it, as if the flesh were an error in divine arithmetic. The irony is that both spent their lives indulging sexuality in two phases — first acceptance, then negation. Gandhi called it self-discipline; in truth, it was self-division — a war between pulse and prayer.

The ashram became a theatre of guilt. A young boy’s heart was turned into an exhibit of sin, and the father’s hunger became his sermon. Here lies the absurdity of saintly moralism: it mistakes natural emotion for temptation and uses piety as punishment.

Tolstoy tormented his wife with confessions of chastity; Gandhi tormented his children with vows of purity. Both built their holiness upon household ashes. The kiss of Manilal should have been forgotten like a passing breeze, but Gandhi turned it into a spiritual storm. And in that storm, the saint reappeared — trembling, absolute, and absurd — fasting against the very life he sought to redeem.

The Kingdom That Denied God

When Russia erupted in 1917, the kingdom of God that Tolstoy imagined turned into a kingdom of ideology. God was negated by the very nation that once trembled before his name. And in India, after Gandhi’s death, prayer meetings turned into political slogans. Both men were consumed by the same absurdity — to blend heaven and earth, the yogi and the ruler, purity and power.

Paul Johnson, in his book Intellectuals, later unmasked this delusion. He wrote how great thinkers, convinced of their moral superiority, often left wreckage behind — neglected families, hollow disciples, burnt ideals. He might well have placed Gandhi beside Tolstoy, both victims of the same metaphysical confusion. The intellect without humility becomes tyranny; the soul without body becomes neurosis.

Both were moral anarchists — dismantling the natural order of life in the name of moral order. Yet their chaos was luminous. They remind us that to seek absolute truth while living in relative life is to walk the razor’s edge.

Tolstoy’s letter to Gandhi was not a gospel; it was a mirror sent across continents — one restless conscience recognising another. Both believed they were bringing God to earth. Instead, they revealed how fragile the divine becomes when trapped inside human flesh.

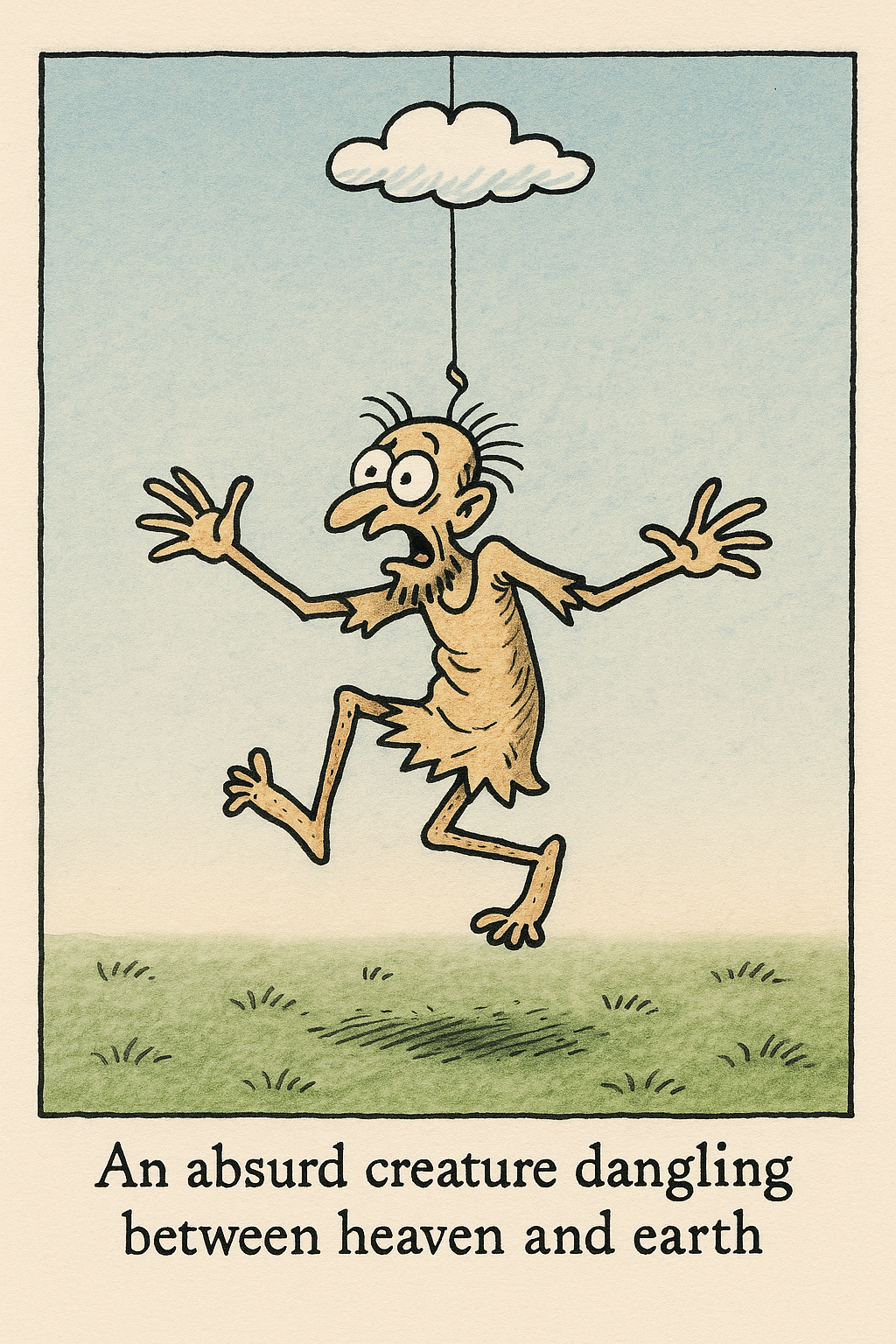

In my view, they were neither saints nor yogis — only half-worn great creatures, persons of nowhere. They tried to walk barefoot on two worlds and tore themselves between them. History remembers their holiness, but time remembers their confusion. Between heaven and earth, they built no kingdom — only the echo of striving souls who mistook restlessness for revelation.

Leave a comment