Recently, the cover of Arundhati Roy’s new memoir Mother Mary Comes to Me stirred a different kind of smoke. She appears on it holding a beedi — calm, defiant, aware of the camera. A Public Interest Litigation in Kerala claimed it violated tobacco laws and sought to ban the book or compel a health warning. The High Court dismissed the plea, saying artistic covers don’t fall under cigarette-pack regulations.

But the image travelled faster than her words. Cigarettes have become the new punctuation of rebellion — small props that whisper, I think beyond you. In an age where gestures compete with ideas, even smoke has turned ideological.

As a doctor, I find it ironic. A cigarette is far more dangerous than it appears — it burns not just the lungs but the will. Smoke it, if you must, but using it on a book cover feels like compensation for the fading strength of the memoir itself. The cigarette becomes a metaphor for exhaustion disguised as style — a symbol of what remains when conviction turns into performance.

There was once a writer in Russia — Nikolai Gogol — who also lived between performance and pain. Critics love to attach him to movements. They call him the forefather of absurdism, the prophet of Kafka, the ghost of postmodernism. It comforts them to find order, as if art were a syllabus. But Gogol never thought in that manner. He was not a theorist of absurdity; he was living it.

He began as a timid, awkward schoolboy, mocked for his long nose, dirty collar, and nervous gestures. Those humiliations never left him. When he wrote The Nose, he was not theorising surrealism — he was trying to cure his own self-loathing. His strange, beak-like nose had become an obsession, a wound that followed him from mirror to mind. And when he wrote, the nose walked out of his face and onto the page. It became a character, a joke, a ghost — his defect turned fable. In that act, Gogol was healed. Pain dissolved in art.

In The Nose (1836), a minor St Petersburg official wakes one morning to find his nose missing — and later sees it strolling the streets dressed as a high-ranking officer. The absurdity unfolds with bureaucratic calm. Nobody questions the logic; the entire city adjusts to the impossible. Then, without reason, the nose returns, and life resumes. That circular, meaningless motion founded a new rhythm in fiction. Without blueprint or theory, Gogol discovered the grammar of the absurd — logic intact but useless, cause and effect preserved but emptied of meaning.

He was not foreseeing postmodernism. He was escaping his own reflection. The twentieth century only gave names to what he felt. No immortal writing begins with philosophy; it begins with ache.

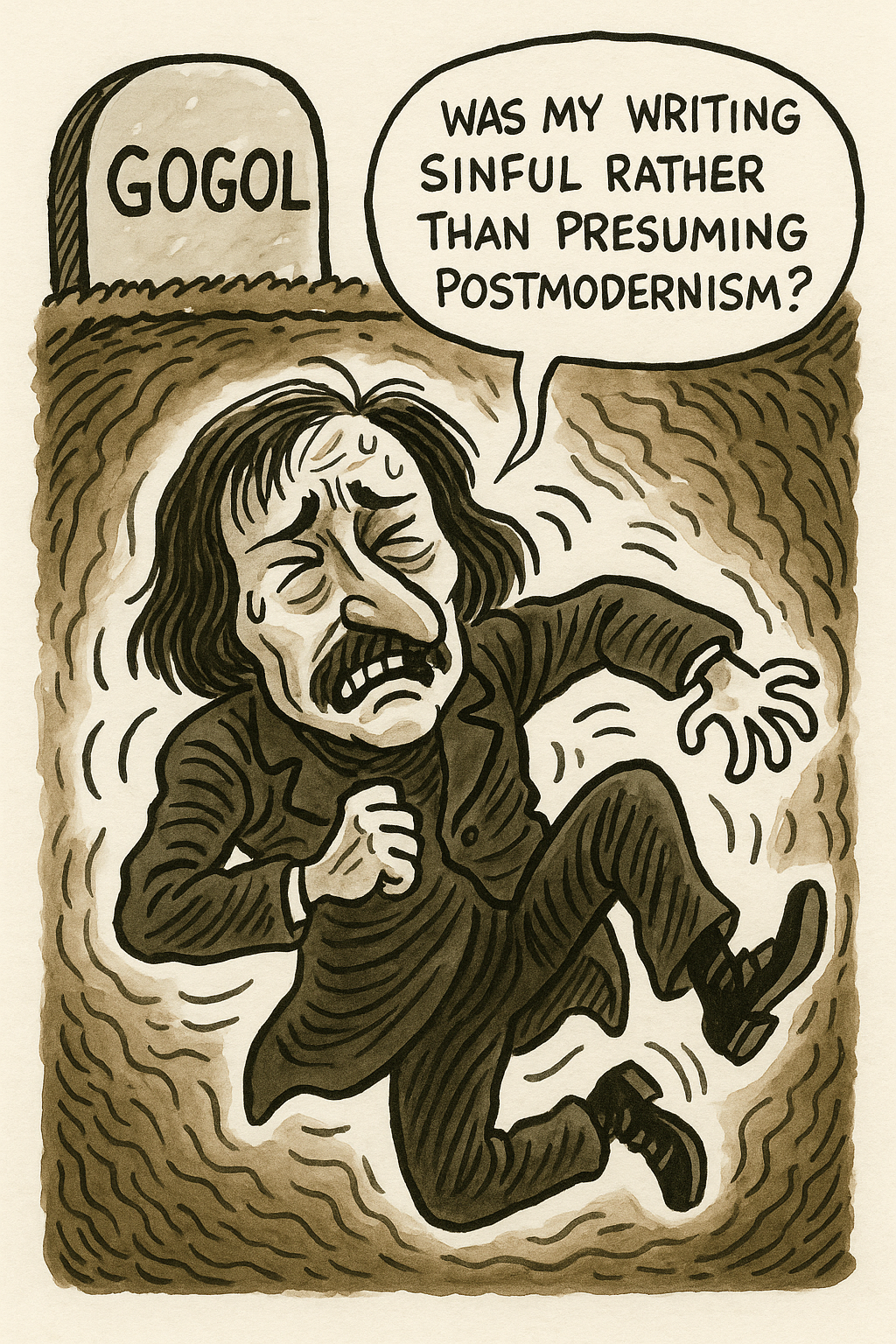

Success did not cure his unrest. As fame grew, his guilt deepened. Under the spell of holy men, Gogol came to see writing as sin. In 1852 he burned the second volume of Dead Souls, believing he was purifying his soul. Soon after, he starved himself to death. When his grave was opened decades later during Soviet reburials, witnesses claimed his skeleton was twisted, his skull turned, the coffin lining torn from within. The rumor spread that Gogol had been buried alive — the final grotesque echo of his own fiction. The man who wrote The Nose and The Inspector General ended trapped between heaven and hell, silenced in both.

Tolstoy followed him into that same wilderness, renouncing literature for moral purity. Both men tried to reform the world after having already illuminated it. They became saints of guilt — artists who mistook redemption for creation.

Arundhati Roy, in her way, echoes that pattern. After one luminous novel, she turned her artistic triumph into a pulpit. The God of Small Things gave her fame; since then, she has written as if purity were superior to craft, as if the forest were wiser than the city. It is a seductive idea, but the forest knows instinct, not dialogue. Civilization, with all its flaws, is still the only structure that allows imagination to survive.

Yet, banning her books — as happened recently in Kashmir, where 25 titles were seized for “false narratives” — is a greater sin than disagreeing with them. A democracy must have the courage to tolerate even its loudest dissenters. The state that fears words exposes its own fragility. Let Roy write what she believes; let others write against her. The page should remain the safest battlefield.

Critics today still cling to labels — modern, postmodern, surreal. They turn living artists into specimens. Gogol, they say, was postmodern before postmodernism. But he was not a prophet of theory; he was a wounded man finding laughter in despair. Every age names its suffering differently. The absurd, the surreal, the existential — these are only new wrappers for an old confusion. What endures is not the definition but the pulse — that trembling rhythm where comedy and pain meet.

Absurdity did not begin with Sartre or Camus; it lived quietly in every human since the first moment someone looked at the sky and found no answer. Gogol felt it instinctively. He did not write to preach but to free himself. His laughter was the nervous laughter of a man watching his own terror dance in the mirror.

And perhaps, somewhere in his twisted grave, Gogol must still be laughing — not about sin, salvation, or postmodernism, but simply about his nose.

#PragyasPen #Gogol #ArundhatiRoy #Absurdism #BookBan #LiteraryReflection

Leave a comment