From my ongoing reflections in “Pragya’s Pen and Perception”—a series on fiction, consciousness, and the dissolving boundaries of narrative.

Where has the plot of fiction gone?

I love Anton Chekhov and Guy De Maupassant’s fiction, they trailed forward in a straight way—sometimes leaped in the past, but their plot and characters went along. In India Premchand’s fictions are descended to the common folks, going well formatted traditional fabric. In my early readings, plot was simply present—unquestioned, not up for discussion.”

At first I was driven to the plot topic after reading Virginia Woolf, who made characters upper hand, and emphasized on the abnegation of plots. Her writing came like a disrupting wave, which uprooted many preconceived rules. Those days were of new milestones—when Sigmind Freud was discovering the human mind through his psychoanalytical tools. Freud gave language to the unconscious mind, but it was not the first ventured episode, Russian writer Dostoevsky had already drilled the inner world—diving into guilt, delirium, and half lit corridors of human thought. In fact Sigmund Freud was greatly inspired by Dostoevsky. And what followed was not a declining story, but the beginning of its disintegration into something more true. To write from the mind—an abstract inkwell—to let characters shape-shift, let events recur without order, in a topsy-turvy trip, and let meaning emerge in fragments. Is it a failure of form? No. It is a deeper fidelity to experience.

If I were to write my story on the traditional track, I would begin with my birth, follow time obediently, and let the characters unfold in sequence. Names would appear, events would occur, places would shift, and the story would move from beginning to middle to end—just as the world teaches us to see and say. This is the outer narrative, the one we dress in facts and calendars.

But the inner world is not a biography. It is a terrain without maps, where chronology crumples. Characters don’t wait for the clock to enter. They enter veiled, twisted, reborn—as memory, metaphor or emotion. In this world—witchcrafts, whispers, images, scents—these summons in vivid way more than any documental detail.

*

How does it happen to me?

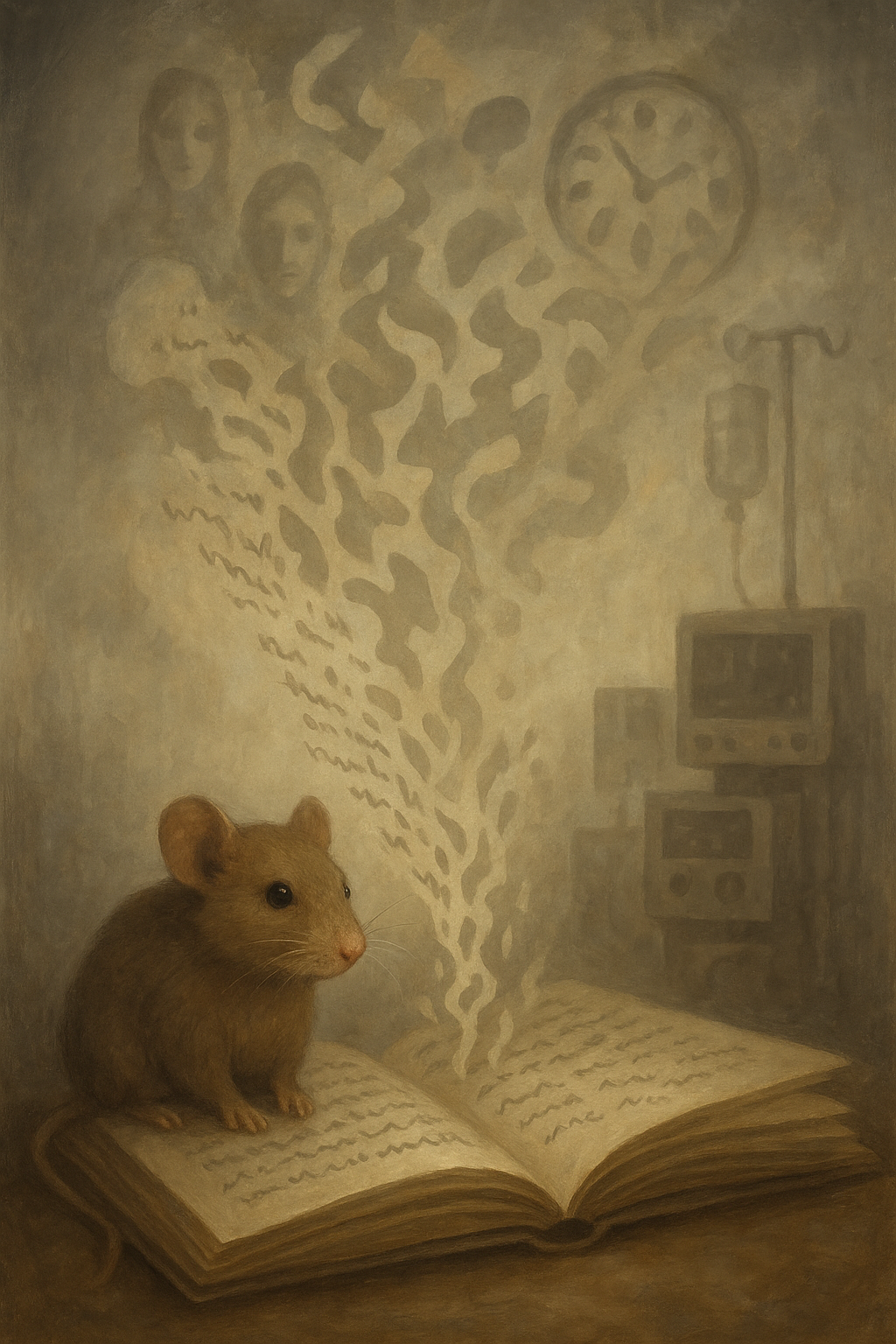

Just yesterday, I heard about a man who was wrongfully operated on by a corporate hospital. A false case, a real body. It was a crime wrapped in protocol, lest non-medic people know it. I have met that person several times. If you see through zoomorphism lense or animal analogies, then human beings’ outlines resemble a particular animal. That man resembled a mouse—short and sloppy. Before the incident I hardly thought about it in my conscious mind. But when that poignant, and soul shattering incident entered my mind—the man did not arrive in his human form. He appeared as a mouse—small, trembling, innocent, with body marks of multiple slices. I imagined it in a flash. Not because I demeaned his pain, but because my mind chose that symbol to express his fragility. In that instant, he was not just a victim; he was a creature surrounded by machines too large, too cold, too indifferent to notice him.

This is the way my mind follows to tell stories. It does not wade through a plot that rises and resolves, but through images that shatters, shivers and dissolves. The plot is not dead, it is diffused into ethereal atoms where the mind frolics. Here the plot is milk and milk’s steam, not the traditional curd. It is sometimes confined in creeks, and becomes scent, texture, shadow. A shard in a wave.

Plot minimalism is often mistaken for emptiness. But it is not empty; it is inward. The mind, after all, is the most agile ocean. Where nothing stays in solid fabric. Where every event breaks apart into colors and echoes. experience.

*

Why did Virginia Woolf’s brilliant mind turn against her?

But the mind, when used constantly as the only stage, begins to blur the line between creation and disintegration. The same ocean that gives us vision can pull us under.

Virginia Woolf knew this. Her work was built from inner weather—shifting moods, time folding upon itself, thoughts too subtle for speech. In her final days, the mind she had so tenderly shaped into fiction turned against her. Schizophrenic manias crept in. She lost the tether to the outer world, and the world lost her. It was not madness alone; it was the exhaustion of a mind too long awake, too long alight.

Artists are prone to this—those who live more vividly within than without. The mind can become so overactive, so luminous, it burns itself. This is the cost of imaginative excess: to feel too much, too deeply, in solitude. Plot dissolves, and sometimes, so does the self.

So the inner writing should be done carefully. Not to avoid intensity, but to hold it with awareness. To return to the surface now and then. To breathe. To remember that even the most fluid dream needs a waking body to carry it.

In the mind’s theatre, plot does not march. It trembles. And we tremble with it.

Note:—This column—‘Pragya’s Pen and Perception”— continues my inquiry into fiction’s evolving form. You can explore the previous posts on the following links:—

https://pragyasumanauthor.com/2025/04/27/pragyas-pen-moral-depth-without-preaching-maupassant-against-tolstoys-hypocrisy/

https://pragyasumanauthor.com/2025/04/20/the-political-machinery-of-the-book-volga-se-ganga-from-volga-to-ganga/

https://pragyasumanauthor.com/2025/04/11/hemingways-lens-what-hemingway-forgot-huck-finn-is-still-a-childrens-classic/

https://pragyasumanauthor.com/2025/03/31/albert-camus-cold-absurdism-vs-philosurreal-postmodern-mystic/

https://pragyasumanauthor.com/2025/03/27/210/

https://pragyasumanauthor.com/2025/03/12/why-is-premchand-not-so-widespread-in-the-world-like-anton-chekhov/

Leave a comment